dwarf fortress, the MoMA, and brainless art criticism

Feb 06 2024

videogames, media, art

A look back on terrible "games-as-art" discourse.

I’ve got a project coming a few months down the line that is broadly in the category of “are video games art?” discourse, and as a result I’ve been reading a great deal of bad faith arguments that argue that the answer is no. One such argument was by The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones in response to the MoMA announcing it will include exhibits on video games in 2012. Of all the cases against video games as art, Jones’s is truthfully one of the worst I’ve ever seen - and I’ve seen quite a few abysmal arguments around this question. He takes the standard position of traditional art critics who are appalled at the debasement of their ivory halls by Pac-Man - namely, that the interactive dimension of video games disqualifies them as artistic works. In his words:

Casting my mind back to the philosophical debate I spied on in Oxford, I remember a pretty good argument for why interactive immersive digital games are NOT art. Walk around the Museum of Modern Art, look at those masterpieces it holds by Picasso and Jackson Pollock, and what you are seeing is a series of personal visions. A work of art is one person’s reaction to life. Any definition of art that robs it of this inner response by a human creator is a worthless definition. Art may be made with a paintbrush or selected as a ready-made, but it has to be an act of personal imagination.

The worlds created by electronic games are more like playgrounds where experience is created by the interaction between a player and a programme. The player cannot claim to impose a personal vision of life on the game, while the creator of the game has ceded that responsibility. No one “owns” the game, so there is no artist, and therefore no work of art.

I genuinely had to keep pieces of my brain from dribbling out of my ears when reading the above paragraphs. Jones - supposedly a respectable art critic at a serious institution - has provided a definition of art that excludes not only video games, but cinema, theater, the overwhelming majority of music, and most literature. It is not a surprise to me that a British art critic at The Guardian has a worldview that essentially endorses the same hyper-individualist “great man” propaganda that I wrote about two weeks ago, but I was just astonished that even in 2012 video games as a medium were held in such contempt that half-baked arguments like these were allowed to go to print without anyone, anywhere stopping to ask the most basic question: “wait, isn’t all art fundamentally collaborative?”

Of course, at the end of the day Jones’s reaction to the MoMA exhibit has nothing to do with some principled position on the definition of art, but a objection to popular gaming culture. Frankly, if Jones’s argument was “gamers are cringe, and I don’t want to be around them in a museum,” I would have much more sympathy for his position. But, like all traditional art critics who unsuccessfully wrestle with the “games-as-art” question, in his unfathomable ignorance he provides a great springboard to talk about actually important observations about our relationship with interactive media.

One of the games featured in the MoMA exhibit that Jones took aim at was Dwarf Fortress. Dwarf Fortress is one of those games that is difficult to succinctly describe without referencing other games that are also difficult to succinctly describe. The best layman’s description I can come up with is “SimCity, but in a Tolkien-esque fantasy world.” That’s still woefully inadequate, as Dwarf Fortress is also one of the most complex social simulations ever created. Unlike SimCity, where the scope of the game is generally limited to one settlement, Dwarf Fortress simulates an entire multi-continent world dotted with hundreds of different settlements, all with different relationships, sizes, races, and cultures.

But far from stopping at simulating the macro-level civilization dynamics, the game is immensely complex on the micro-level as well, with each citizen having their own set of personality traits, family and friends, occupations, interests, and as we’ll discuss more later, pleasant memories and foundational traumas. I have never played any strategy or simulation game that demands more attention to the mental health of your subjects than Dwarf Fortress. Unlike in Civilization or SimCity, where the “moods” of your population are only calculated on the society-level, Dwarf Fortress has a running tally on the emotional state of every dwarf in your fortress that’s given such pride and place that it is listed before your total stocks of food and water.

This level of granularity in the game’s social simulation - which has been in active development since 2002 - has made Dwarf Fortress a kind of generative story engine. On one level, you have the superficial “goals” of the game: build a big fortress, trade to increase your wealth, don’t get slaughtered by dragons. But that is just the base layer of interaction you need to get a handle on before you access the part of Dwarf Fortress that has given it the staying power it needed to survive over two decades. The real attraction of the game is the way it can manage to get you invested in the inner world of a guy who looks like this:

A screenshot of a dwarf, taken from the Bay 12 Games website.

A screenshot of a dwarf, taken from the Bay 12 Games website.

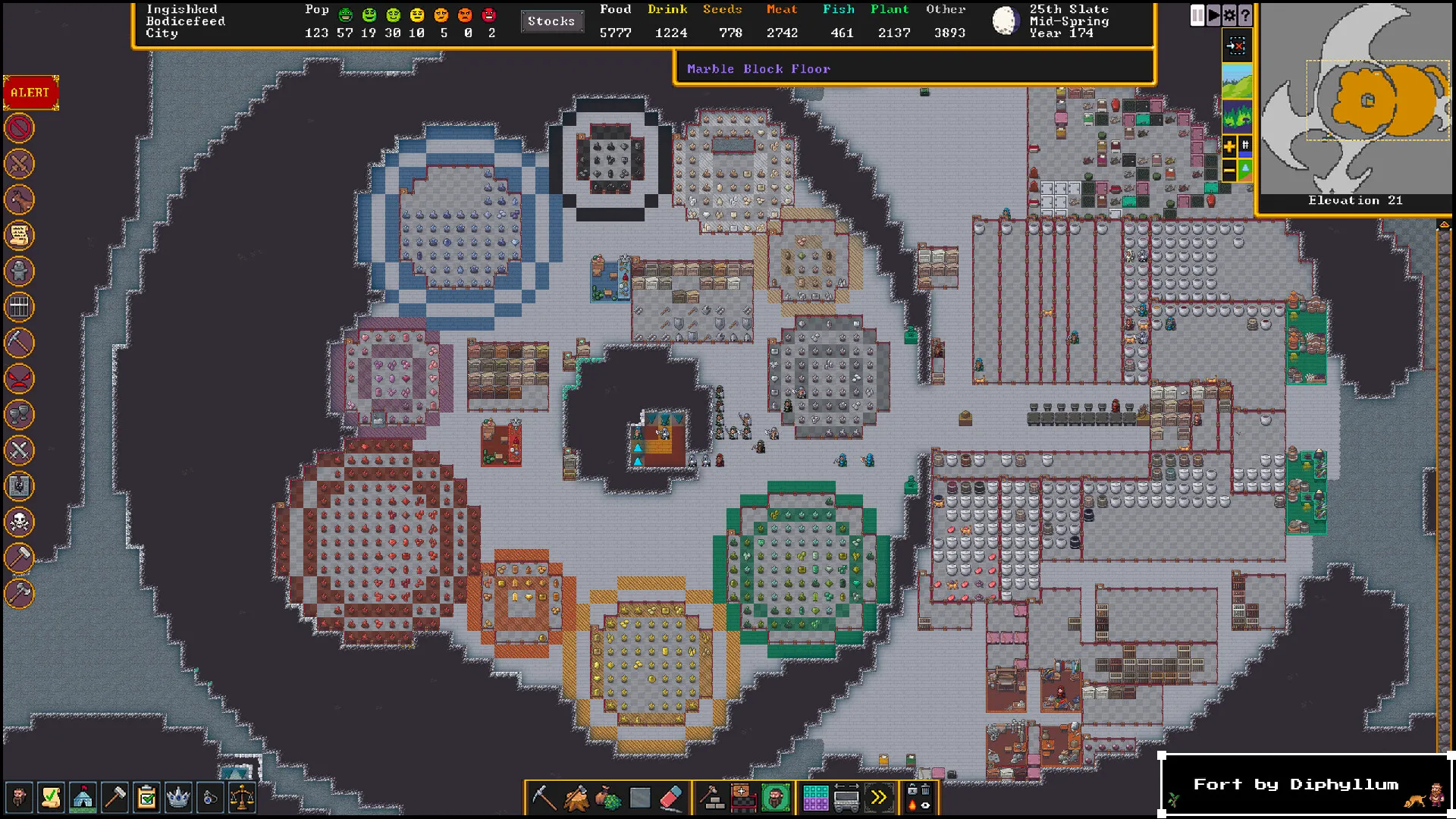

Now, you’re probably wondering: “what the fuck am I looking at?” I’m wondering too. Frankly, I’m not even sure if that smiley face in the middle is a dwarf or not. The screenshot above is from the old ASCII version of the game, and it reveals the catch to Dwarf Fortress’s complexity. The reason why the game - developed by only two people until very recently - is able to be so complex is that the graphics are fashioned out of leaves and fishing twine (text-based graphics and basically no diegetic sounds), meaning that adding new creatures and mechanics can be done rapidly without having to worry about the costs of a bloated art pipeline. Even in the modern Steam release (the one that got me into the game) the sprites and animations are kept pretty sparse:

A screenshot from the 2022 Steam release taken from the game’s Steam page.

A screenshot from the 2022 Steam release taken from the game’s Steam page.

With this spartan aesthetic presentation in mind, all the game has to rely on to get you invested in its little gremlins is text - and there is a lot of text. Each dwarf has a running log of emotions and thoughts that update in real time, and each contains a “personality” menu that gives a brief overview of their personal history that also updates in response to events that occur within the course of your playthrough.

At first, when you’re learning the game, you won’t have the mental capacity to keep an eye on how any individual dwarf is doing - you’ll be too busy wrestling with the UI and focusing on not starving through the winter. This will remain the case until you’re confronted with any of the myriad tragedies that can completely obliterate your fortress: goblin raids from nearby lands, forgotten beasts emerging from the depths, or even something as typical as a freak construction accident. With experience and preparation, these disturbances can be mitigated and handled in an orderly manner, but during your first playthrough they will almost certainly be cataclysmic in scale. It is not unusual in the first dozen hours or so to have an incident that kills well over half of the population of your fortress. In any colony management game, having half of your citizens die in five minutes is, to use a technical term, “bad.” But unlike most games of its ilk, the cyclical tragedy of Dwarf Fortress is a key part of the intended emotional experience.

The official motto of Dwarf Fortress is “losing is fun.” Personally, I would amend that statement to “losing is interesting,” but the spirit of the motto refers to the way that Dwarf Fortress is as much about rebuilding as it is building. Despite the perils mentioned, it is actually quite rare for a fortress to suffer a complete extermination. As a result, your first real connections to your dwarves will be forged through hardship and tragedy, as you steward them through the aftermath of this or that calamity, create tombs for their dead, and nurse their wounded. Dwarves that survive great tragedy do not continue plodding along in their lives as if nothing happened. The trauma they experience - physical and mental - is carried with them through the rest of their lives. It affects the way they approach their fellow survivors, future relationships, and their own conception of their place in the world. And this process of wrestling with the weight of these events extends well past the lives of the dwarves who witness it, as these tragedies (and occasional triumphs) themselves become historical events that are immortalized in in-game engravings, statues, and literature. This process is made all the more intimate by the fact that you, the player, were there to witness it, and depending on the catastrophe in question, you may even be culpable in it.

This dynamic engenders a feeling of responsibility that is not present in other large-scale colony simulators or strategy games. Throughout the game’s two decade history, its players have compulsively documented the stories that take place in the fortresses they steward, whether it be the tale of an individual mythic hero or the history of a whole society. This compulsion comes from a very deep human impulse - the same impulse that motivated the cave painters and the myth-makers of old. It is not uncommon to spend dozens of hours on a single fortress at a time; some players have worlds that they have been documenting for over a decade. Once you get over the (quite sizable) hump of the game’s interface, it becomes almost impossible to not begin keeping track of the lives of notable individuals around your fortress. You watch mayors become barons and then kings, you watch children become adults, you watch recruits become warriors, and you watch splendor become ash. And you do so again, and again, each story building atop the last, the echoes of the past fading into the background but never quite disappearing.

None of this is an accident. There are plenty of specific phenomena in Dwarf Fortress that are organic outgrowths of the simulation, but even with this in mind, almost every story that Dwarf Fortress generates tackles the same broad themes: the hubris created by wealth, the indifference of the universe to tragedy, and most importantly: the indomitable will of the human dwarven spirit. Its thematic through-lines are so strong and defined that they persist through every single one of the game’s randomly generated worlds.

This is, among other reasons, why Jonathan Jones’s assertion that game developers have “ceded the responsibility” of imposing a “personal vision” onto their works is completely ludicrous. Dwarf Fortress absolutely has an artistic vision that it imposes onto every world it creates, and the mechanics contained within it are not merely the trappings of a “playground” as Jones describes, but statements about civilization, loss, and human nature.

And, I mean, all of this is immediately obvious to anyone who has actually engaged with video games as artistic works. Obviously, any simulation of society or culture must make some kind of statement about society or culture, and those statements are necessarily charged with political and philosophical meaning. Dan Olson dived into this idea beautifully in his video about how Minecraft (another game featured in the MoMA) and the sandbox genre indulge in the fantasy of “clean” colonialism, and Jacob Geller does the same in his video about how different artistic works tackle the climate crisis. Video games - with their unique ability to transform their players into actors rather than merely witnesses - are absolutely at the artistic frontier of tackling questions of social responsibility, free will, and subjective reality. And the depth and complexity of the medium is going to continue to advance unabated despite the objections of Guardian op-ed writers, which underscores the importance of learning to engage with and understand them as art.

In the middle of his polemic, Jones writes:

I first encountered this trope of the inappropriate elder’s interest in the newest games a few years ago at a philosophy conference in Oxford University (I was an interloper in those hallowed groves). An aesthetician – a philosopher who specialises in aesthetics – gave a talk on his research into games. He defended them as serious works of art. The art of games, he argued, if I understood him right, lies in their interactive dimension and liberation of shared authorship. But he never answered the question: what was a professor doing playing all these games?

As I hope I’ve made clear, the answer to Jones’s question is simple: the professor was taking his job seriously. I recommend Jones give it a try sometime.