akira toriyama taught us how to beat god in a fight

Mar 19 2024

media, anime

And, for most of us, it worked.

On the first of March, Akira Toriyama, the creator of Dragon Ball, passed away. I have read, watched, and listened to a great many eulogies for the man across dozens of publications, and every single one I have read has felt like it has understated his impact. I will proceed to do the same.

This is not due to a lack of care - Toriyama’s impact on culture the world over is so immense that it is genuinely difficult to wrap one’s head around. There is no person more singularly responsible for popularizing Japanese animation and culture around the world, and the absolutely pivotal role that Dragon Ball had in shaping literal generations of artists, musicians, writers, game developers, and animators is second only to cultural titans like Bruce Lee.

I struggle to remember a time in my life where I didn’t know about Dragon Ball. Like many things, I’m sure I was introduced to it by my older cousin who had seen the original Western airing of it in the 90s, but by the time the remastered Kai version began airing on Nicktoons, I already had a keen awareness of the show’s characters and plot. By the age of ten, I was already completely enraptured by the series, and devoured any piece of TV, movies, or games from it I could get my hands on. After I had watched everything that was available on Nicktoons, my desire to watch the Cell saga was what motivated me to learn how to search for alternative sources of media on the internet at a young age.

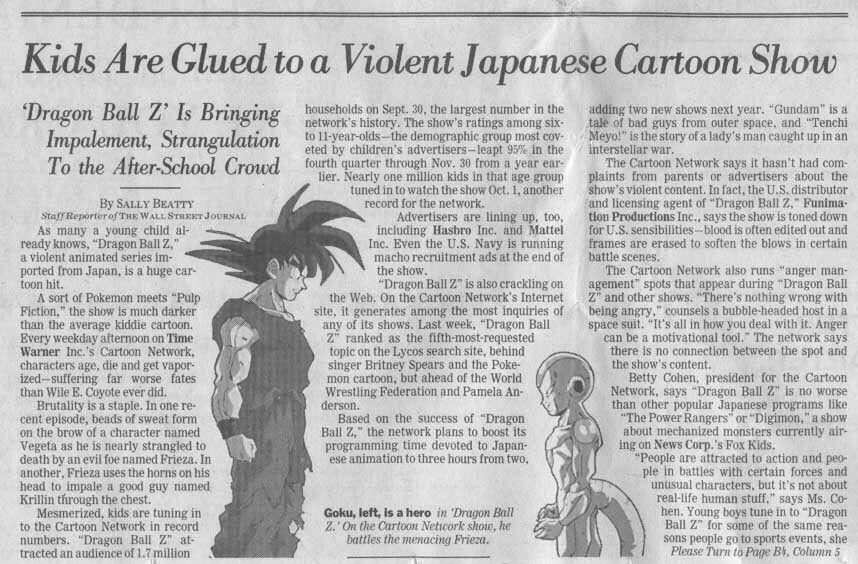

A now famous article from The Wall Street Journal published during the show’s original airing in the 90’s. It underscores how unique the show was compared to anything else on children’s television at the time.

A now famous article from The Wall Street Journal published during the show’s original airing in the 90’s. It underscores how unique the show was compared to anything else on children’s television at the time.

The superficial appeal of Dragon Ball is obvious: it’s awesome. It is the most violent spectacle that is available on children’s television. It is a show that is relentlessly committed to the drama of combat, with ever-escalating duels between god-like beings (and eventually literal gods) punctuated by punches that can smash mountains and energy blasts that can destroy planets. But this isn’t the whole story, because for all of Dragon Ball (and Toriyama’s) characteristic silliness, there is a genuinely profound spiritual undercurrent that the show has that has given it the mythological resonance it has worldwide.

Dragon Ball is, at its core, a story about the endless development of the self. This is most exemplified by the dynamic between the show’s most popular characters: Goku and Vegeta.

At the beginning of Dragon Ball Z, Goku and rival-turned-ally Piccolo confront the show’s first villain: Raditz, a powerful alien invader and Goku’s estranged brother. At the end of the fight, Goku sacrifices his life both to defeat Raditz and rescue his son. It is notable that the very first fight in Dragon Ball Z ends with Goku dying. Immediately we are introduced to a hero who -unlike other Superman-inspired protagonists - is decidedly vulnerable. He’s so vulnerable, in fact, that the entirety of the next arc centers around him training in the afterlife in preparation for the arrival of Raditz’s comrade: the legendary Saiyan prince Vegeta.

Vegeta, in sharp contrast to Goku, derives his strength not from training but from his birthright. He is a proud, unapologetic eugenicist, and upon their eventual confrontation he makes immediately clear that he sees Goku as socially and genetically inferior. The fact that Goku has trained for an entire year and been given special permission by the Gods to return to the land of the living doesn’t phase him for a moment. He sees the self as something immutable, and he sees the process of trying to improve it not only as useless, but an active affront to the natural order.

This is, of course, until Goku beats his ass.

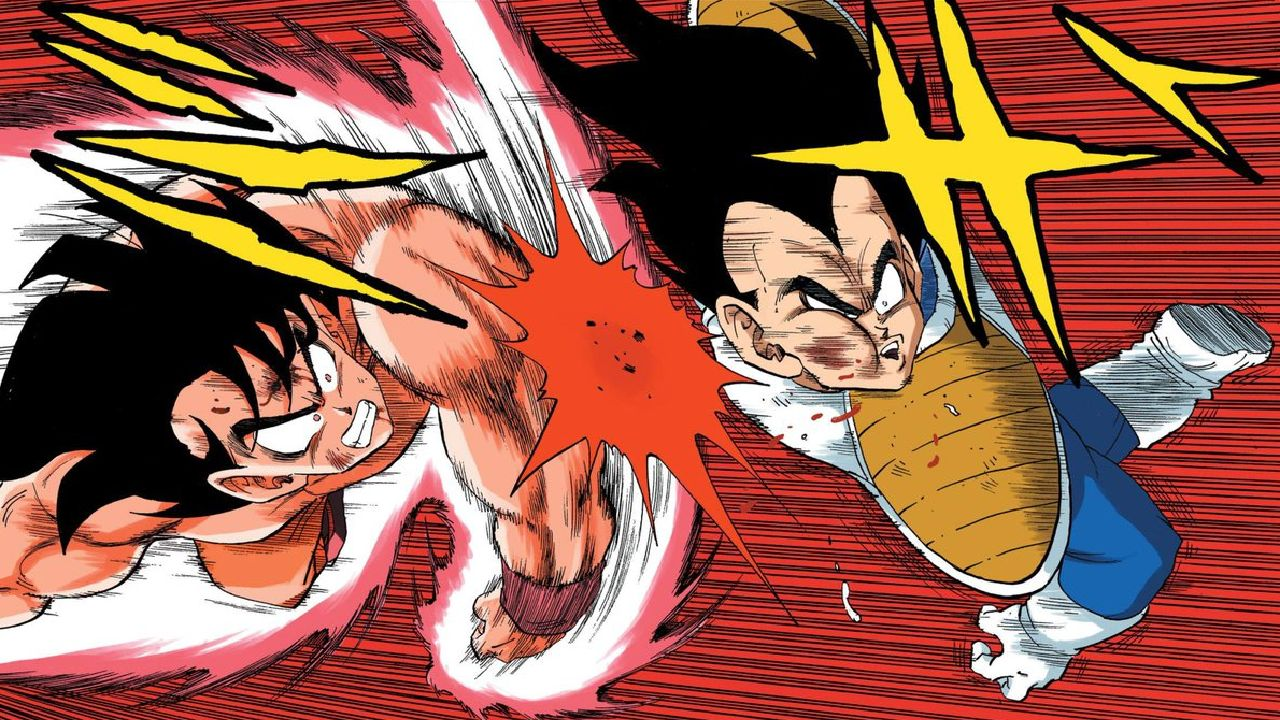

One of many legendary frames of the first Goku vs. Vegeta fight from the original Dragon Ball manga.

One of many legendary frames of the first Goku vs. Vegeta fight from the original Dragon Ball manga.

Vegeta escapes the fight with his life, but this defeat will hover over his head for the rest of the entire show. Goku did not just destroy his body, but he destroyed his worldview. Vegeta - the crown prince of his warrior race - was brought low by the son of a common soldier who was raised by a country bumpkin from the mountains. The brutal reality of this fact begins to transform him completely. Before too long, it’s Vegeta who is the one that is spending time training around the clock in order to surpass Goku.

But importantly, Goku does not regard the brief moments that Vegeta - or any of his foes - surpass him as an affront to his honor. He’s excited. Goku has, on several occasions, spared the lives of major villains (including Vegeta) in the hopes that not only they improve as people, but that they improve as sparring partners. The prospect of being the strongest man in the universe - a thing he has actually achieved at various points in the show - is boring to him. He is, more than any other hero in fiction, relentlessly and single-mindedly dedicated to the journey rather than the destination.

It’s hard to overstate how much of an impression Goku’s worldview made on me at a young age. The show, unsurprisingly, validates his worldview at every turn with an immense amount of pomp and circumstance. The reason why almost anyone who watched the show has attempted one of its iconic techniques in real life is because the story is genuinely bombastic and earnest enough to make you believe that you could beat God in a fight if you spent enough time in the gym. Dragon Ball teaches you to find opportunity in failure and humility in victory. It treats combat not as a zero-sum competition for dominance or as an expression of malice, but as the highest expression of love and respect. And, most importantly, it teaches you to find the beauty in the journey. And, after all, what could be a more appropriate a story to tell from a man who spent every week for 40 years honing his craft to absolute perfection?

For decades, Toriyama made us believe that there was no barrier that effort could not break. And in his work and in his life, he proved it. For that, I can’t thank him enough.